ąÜąĮąĖą│ą░ ąĪą░ą╣ą╝ąŠąĮą░ ąĪą┐ąĄąĮčüą░

ąÜąĮąĖą│ą░ ąĪą░ą╣ą╝ąŠąĮą░ ąĪą┐ąĄąĮčüą░

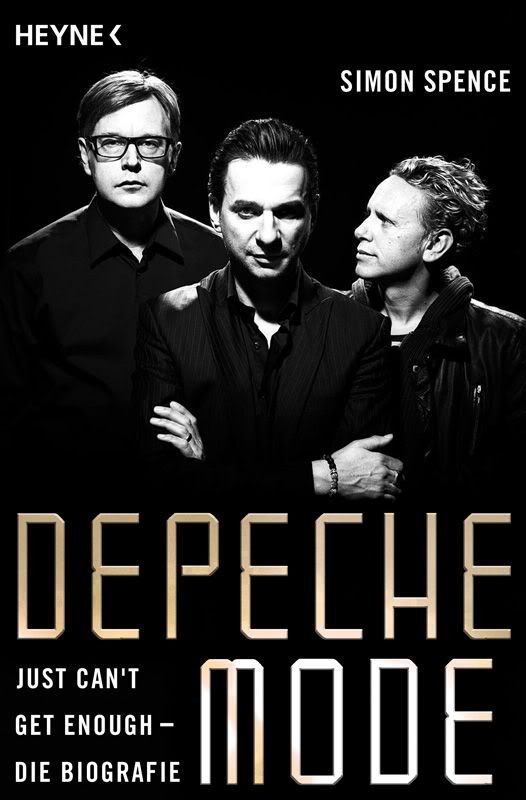

Just Can't Get Enough: The Making of Depeche Mode A Jawbone Book

First Edition 2011 (15 October, 2011)

Published in the UK and the USA by Jawbone Press

ISBN 978-1-906002-69-5

EAN: 978-1906002565

ISBN 10: 1-906002568

REF: BTR-1906002568

Editor: Thomas Jerome Seabrook

Jacket photograph: Virginia Turbett/Redferns/Getty Images

Volume copyright ┬® 2011 Outline Press Ltd. Text copyright ┬® Simon Spence.

ą¤čĆąĄą┤ąĖčüą╗ąŠą▓ąĖąĄ ąĖ ą¤ąĄčĆą▓ą░čÅ ąōą╗ą░ą▓ą░ (ą▒ąĄąĘ ą┐ąĄčĆąĄą▓ąŠą┤ą░)PREFACE

I canŌĆÖt recall when or why I first got into Depeche Mode, but by the time of Black Celebration in 1986 I had all their albums. No one else I knew liked them. I was 16.

I do know that by the time I joined the NME as a writer in 1989 IŌĆÖd sold the lot, and it canŌĆÖt just have been to fund the drug habit. I can still remember selling my vinyl copy of Speak & Spell. I had handwritten what I thought were the song lyrics on a sheet of A4 paper, slipped it inside the sleeve, and forgotten all about it ŌĆō until, after checking the vinyl, the record shop guy sneeringly handed back that relic of my teenage infatuation.

I had collected all the seven-inch singles, too, up to and including ŌĆśShake The DiseaseŌĆÖ. All sold too, regrettably. I saw them live for the first and only time on the Black Celebration tour. I know what I wore. A girl at school I had a crush on loaned me her black leather trousers and I coupled them with some sort of black fake-leather belted overcoat bought in a charity shop. No doubt I was caked in make-up.

My most vivid memory of the band from this period was of the blonde candyfloss-haired Martin Gore, in a leather skirt and black diaphanous womanŌĆÖs slip, handcuffs dangling casually by his side, as he played a bicycle wheel on Top Of The Pops for ŌĆśBlasphemous RumoursŌĆÖ. It was almost as sweet and as illicit a thrill as slipping into those leather trousers.

I liked Dave Gahan too. He wasnŌĆÖt as subversive as Gore but his hair was easier to copy: the flat-top with the blonde highlights at the front. It was a disaster on me. Maybe that was what brought an end to my Depeche Mode period.

Looking back, it was, in truth, about more than the hair (although I could never like a band with bad hair). Depeche Mode had never been perceived as cool ŌĆō according to John McCready of The Face, they were ŌĆ£second only to the combined forces of Kylie, Cliff, and PWL when it comes to being subjected to the acid wit of the pop mediaŌĆØ ŌĆō and in my late teens I was desperately subsumed by the desire to be cool.

I donŌĆÖt know if I was embarrassed by them, but I certainly never mentioned my teen love for the band as I scribbled my way across the NME, The Face, and i-D, covering bands such as The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, and Primal Scream. Not even when Vince Clarke remixed The Happy MondaysŌĆÖ ŌĆśWrote For LuckŌĆÖ and transformed it into a classic.

As the 90s progressed I just forgot all about them. It seems I wasnŌĆÖt the only one. Ironically, the more famous they became in America and Europe during that decade, the lower their profile in the UK. It was only after I began research for this book that I realised just how well they had done without me.

Twelve studio albums, a handful of greatest-hits packages, four live albums, innumerable videos, and one great feature film; Depeche Mode are now officially one of the ten best-selling British acts of all time, sitting pretty alongside such exalted company as The Beatles, the Stones, Led Zeppelin, and David Bowie. And, after 30 years together, they continue to grow in popularity.

On their 2005ŌĆō06 and 2009ŌĆō10 world tours they played to over five million people in 32 countries. Their most recent studio album, 2009ŌĆÖs Sounds Of The Universe, went to Number One in 21 countries. In America they are giants, playing stadiums, topping the Billboard charts, and winning Grammy nominations. In Europe they are closer to being Gods, revered from East to West by a devoted mass of ŌĆśalternativeŌĆÖ youth, their own ŌĆśblack swarmŌĆÖ cult. In 2006, the iTunes Music Store released The Complete Depeche Mode as its fourth ever digital boxed-set, following on from similar packages of music by U2, Stevie Wonder, and Bob Dylan. ThatŌĆÖs not bad company to keep.

In their homeland, however, Depeche Mode have never really won over the critical cognoscenti. Here, perhaps, is the biggest band in the world, certainly the most worshipped, and yet their achievements and significance go broadly unreported in the UK. People ask whether they are still going, or remember that they were once huge in Germany. This has, understandably, long troubled the band.

In the late 80s, Martin Gore pondered the question of why the band had not been given the respect they deserved in the UK. He thought the current crop of music journalists were too stuck in rockŌĆÖs past; it would take a new generation of writers to come along for his band to be truly, critically appreciated.

More than 20 years later, perhaps, there is a sense that the attitude toward Depeche Mode is softening in this country. Some new faces have begun to hold cultural currency in the UK media; reappraisal of the group is slowly beginning. Video artist Chris Cunningham, for instance, explicitly referenced Speak & Spell in one of his acclaimed artworks, while in 2008, Turner Prize winner Jeremy Deller co-directed a documentary about the bandŌĆÖs fans, The Pictures Came From The Walls.

But Gore is still waiting for someone to truly capture and rapture the band in print. In a sense, Depeche Mode are still waiting to be truly discovered. Paul Morley, in his liner notes for Depeche Mode: The Best Of Volume 1, floated the idea that the band were the Rolling Stones of their generation. IŌĆÖd say they were more like The Who ŌĆō not just in the way Townshend writes for Daltrey as Gore writes for Gahan, but in the way both bands represent something else, something more than music. The Who started to dismantle rock with their ŌĆśwe are artŌĆÖ stance, and Depeche Mode cast the parts to the wind with their mantra, reductive of punkŌĆÖs ŌĆśthree chords is all you needŌĆÖ: ŌĆśone finger is all you needŌĆÖ.

Pete Townshend once told me how he felt The Rolling Stones had built a ŌĆ£massive fucking wallŌĆØ between one generation and the next ŌĆō ŌĆ£no more singing silly love songsŌĆØ. Depeche Mode built another huge fucking wall. No more silly guitars.

Going back to them now, looking at those first five albums afresh, itŌĆÖs hard to understand their struggle for credibility. Maybe they were just too far ahead of their time, as Gore suggested. The line-up was easy to decipher ŌĆō the bubblegum dream of four teenage kids ŌĆō but everything else about them was like nothing that had been seen before.

Perhaps their attitude, so anti-rock in every way, was the barrier. They certainly did a lot of uncool pop TV ŌĆō but never as anything but themselves. The tunes surpassed pop: ŌĆśJust CanŌĆÖt Get EnoughŌĆÖ is virtually a national anthem, a terrace anthem for Celtic and Liverpool fans. ŌĆśMaster & ServantŌĆÖ matches ŌĆśVenus In FursŌĆÖ for lyrical and sonic subversion. Their second album, A Broken Frame, is wildly esoteric. Some Great Reward and Black Celebration broke electronic boundaries.

But it was that first album I initially returned to. The CD comes with a lyric sheet now. I still love it: itŌĆÖs camp, weird, catchy ŌĆō a new world of sound. My idea was to reappraise 1981ŌĆÖs Speak & Spell and hail it as one the greatest British albums of all time. In fact, I would argue that it was a landmark work, a game-changing album comparable to the first Velvet Underground LP.

Originally, the book would have covered the conception of their deeply influential hometown of Basildon, traced their youth and coming together as a band, and ended with the last note of that first album. Now, IŌĆÖm glad to have continued to follow the bandŌĆÖs journey until their massive 1986 Black Celebration world tour. That was five more years of ammunition to suggest that Depeche Mode broke ground in a way few other British acts before them had, maybe just The Shadows or Roxy Music, and that they were every bit as redolent of their times as Pink Floyd or the Sex Pistols.

True, they were not the first all-synth act (and they have since mellowed toward guitars) but in the words of Seymour Stein, the president of Sire Records who rushed to sign the group in 1981, and whose other discoveries include Madonna, Talking Heads, and The Ramones, Depeche Mode were the first electronic outfit that ŌĆ£fucking rockedŌĆØ.

But it was not just their music or live shows that made them unique: it was the way they approached making their music and the way they delivered and managed their output too. Everything about them was so ultra-modern, even their sexuality. They were the first word in post-modernism.

I wanted to exhume and re-evaluate the early career of Depeche Mode, to wallow in and celebrate it, elevate it to its true level, above what is commonly remembered, in John McCreadyŌĆÖs words, as ŌĆ£two parts jokes about leather skirts, one part references to their New Romantic tea-towel-wearing period, and several gratuitous references to BasildonŌĆØ.

In the period this book now covers, Depeche Mode conquered the world and put in place a team and a way of working that would provide the bedrock for the next two decades of their record-breaking career. This book explains how and why.

There was certainly no envisaging that places such as Argentina, Mexico, Israel, Colombia, Peru, Chile, Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Germany, France, Italy, Sweden, Ukraine, Spain, Portugal, Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Hungary, Turkey, Finland, Romania, and on and on and on would all feature on the bandŌĆÖs juggernaut, multi-million-dollar world tours when, in 1980, they first set up their cheap synths and an even cheaper drum machine on tables and beer crates and sang of feeling like a television set in front of their trendy clique of 50-odd fans in Basildon, Essex.

But the Depeche Mode story starts before that, with another black swarm: a black swarm of World War II German bombers and fighters, flying across the Channel, following the Thames estuary up to London and beginning their apocalyptic devastation of the capital.

The story starts with Basildon.

PART 1: GENESIS

CHAPTER 1: THE MASTER PLAN

To really understand Depeche Mode we need to really understand Basildon, the Petri dish in which the group were formed. It was the so-called city of the future, built from nothing out of the mud in the aftermath of World War II. This artificial settlement, intended for around 80,000 people, was created to provide homes for East London overspill and make good an area that was unfit for modern living. The broader consequences of what was from the outset described as a ŌĆ£bold social experimentŌĆØ were unknowable.

The members of Depeche Mode were from the very first generation of kids to grow up in this experimental New Town. It seemed obvious that the kind of music Vince Clarke, Martin Gore, Andrew Fletcher, and Dave Gahan found fame playing ŌĆō a brutal onslaught of processed newness ŌĆō must have been informed by their Basildon childhoods, and none of the original band members have denied it.

Basildon was conceived as a kind of utopia for the working classes, with green open spaces, luxury housing, and a plentiful supply of jobs. Plastics, electronics, cars, and other things of the future would be made in modern factories by happy workers living a new, healthy, better life. Like the music of Depeche Mode, Basildon was all about innovation, modernism, and progress, and free of grime and ugliness.

The future was being reborn, and these four young men were lab rats in a truly alien landscape. It was no surprise that when they first made it out of Basildon, the London music press described the group as ŌĆ£half-MartianŌĆØ ŌĆō or that, when they first found their fame, it was as part of a movement called the Futurists.

To really understand Basildon, we really need to speak to Peter Lucas, whose three books on the subject provide the definitive historical word on the creation and development of the New Town. Unfortunately, his previous employers, Basildon council and the Evening Echo, the local newspaper, responded to my enquires with the news that in all likelihood Peter had passed away. He and his wife had lived in Portugal for a while before returning to the UK to retire in Dovercourt, Essex. But that was about ten years ago; nobody had heard from him since.

Judging by the author picture in Basildon: Birth Of A City, published in 1986, IŌĆÖd guess the current age of Peter, if he were still living, to be just north of 80. After a little digging, I found an address for a Peter Lucas in Dovercourt. The age demographic matched; the house had been bought in 2001, but was sold in May 2010. The telephone number was ex-directory, so all I could do was write a letter to the present occupiers and wait.

Even PeterŌĆÖs three books on Basildon ŌĆō Basildon: Behind The Headlines (1985), the aforementioned Basildon: Birth Of A City, and Basildon (1991) ŌĆō are hard to find. The publishers have long since lost contact with the author. Reading these books, I was reminded of an early line from Dave Gahan describing Depeche Mode as ŌĆ£a new sort of band from a new sort of townŌĆØ. A similar theme was raised by Robert Marlow, a close friend of the band who came within a whisker of making it into the final band line-up. He described the sound of Basildon, the Depeche sound, as ŌĆ£coming out of the New Town bricksŌĆØ.

That very first New Town brick was laid by the Lord Lieutenant of Essex, Sir Francis Whitmore, in a ceremony held on November 10 1950. It was the foundation stone for the South East Essex Wholesale Dairies on the evocatively titled Industrial Estate Number One. The ceremony coincided with the publication of the first Basildon Master Plan, produced by the secretive Basildon Development Corporation; a plan catering for a proposed population of 83,700 in what was dubbed ŌĆ£the first City for the 21st centuryŌĆØ.

The New Towns Act had been introduced in 1946 by the newly elected Labour government. The Act was part of Clement AtleeŌĆÖs partyŌĆÖs ambitious post-war vision for a better future for the country, alongside the creation of the welfare state and the NHS. Two years later, on May 25 1948, the Minister of Town and Planning, Lewis Silken, announced provisional approval for the setting of an 11th New Town, in the Basildon area, with a population of 50,000.

The countryŌĆÖs leading town planner, Professor Sir Patrick Abercrombie, drew on the principles of the Garden City Movement and the modernist movement in proposing to reduce the population of London by moving over half a million people to New Towns located in an orbit around the capital, just beyond the green belt.

These New Towns were planned as self-contained communities with employment provided by tailor-made factories ŌĆō places where businesses could be given the space to expand and where workers would benefit from being freed from the daily commute. The logic was persuasive, suggesting both that the UK was open for business and forward-looking, and that there was an alternative to rank, overcrowded inner-city conditions. This was the beginning of the modern age.

Introducing the New Towns Act, Silken said: ŌĆ£We may well produce in these New Towns a new type of citizen, a healthy, self-respecting dignified person with a sense of beauty, culture, and civic pride. I want to see New Towns gay and bright ŌĆō they must be beautiful. Here is the grand chance for the creation of a new architecture. We must develop in those who live in the New Towns an appreciation of beauty. The New Towns can be an experiment in design as well as into living.ŌĆØ

Between 1946 and 1950, eight satellite towns for London were designated: Stevenage, Hemel Hempstead, Hatfield, and Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire; Crawley in Sussex; Harlow and Basildon in Essex; and Bracknell in Berkshire. Six more were planned for the rest of the UK. It was reported that each one would cost around ┬Ż10 million, and that their development would take 20 years. This was an inspired guess at best. In 1970, Silken admitted: ŌĆ£We had no real knowledge of the organisation and finance required [to create the New Towns] nor could we readily see the social problems that might emerge.ŌĆØ

Each New Town was to be built by a specially appointed Development Corporation that had legal powers to compulsory-purchase land in the ŌĆ£designated areasŌĆØ at agricultural value and to grant planning permission. In effect we were talking about large-scale land nationalisation, and the largest public housing building programme of its kind.

The New Towns were heavily promoted as a giant leap into the future ŌĆō a move away from polluted, unhealthy, and dysfunctional slums dominated by smokestack factories to an era defined by clean, walk-to-work neighbourhoods, zoned living, green spaces, and leisure. The image sold to the public was of modern, morale-raising, bright, clean, white, light, and airy apartment blocks, schools, and hospitals rising from bombed out Victorian slums.

ŌĆ£It is not enough in our handiwork to avoid the mistakes and omissions of the past,ŌĆØ announced Lord Reith, the former Director General of the BBC turned Chairman of the New Towns Committee. ŌĆ£Our responsibility, as we see it, is rather to conduct an essay on civilization, by seizing an opportunity to design, evolve, and carry into execution for the benefit of coming generations the means for a happy and gracious way of life.ŌĆØ

The rhetoric of Silken and Reith fell on deaf ears in Stevenage, the first designated New Town. Here there was tough opposition from the existing 7,000 inhabitants, who strongly objected to the thought of having a further 70,000 people ŌĆō urban slum-dwellers, no less ŌĆō plonked on top of them. Local author E.M. Forster declared that the New Town would be ŌĆ£like a meteorite upon the ancient and delicate scenery of HertfordshireŌĆØ. There were further legal challenges to block the creation of the proposed New Towns in Crawley, Hemel Hempstead, and Harlow.

In the media, Silken quickly acquired the nickname ŌĆśSilkengradŌĆÖ, in reference to Soviet authoritarianism. Others took a broader view. As the esteemed Frederick Osborn put it, with sound reason: ŌĆ£The urban many should outweigh the desires of rural few.ŌĆØ

Osborn had been the right-hand man of Ebenezer Howard, the founder of the Garden City Movement, on which many of the ideals of the New Town Act were based. In fact, the success of HowardŌĆÖs Garden City of Letchworth, completed in 1926, had already impacted on town planning and the British landscape. In the aftermath of World War I, the government had interpreted part of HowardŌĆÖs thinking in the outward expansion of existing cities and the creation of vast new suburbs.

There were pockets of success for HowardŌĆÖs advocates. For instance, Hampstead Garden Suburb ŌĆō where the man behind early Depeche Mode, Mute record-label boss Daniel Miller, grew up ŌĆō retained the spiritual undertones of the Garden City Movement with romantics and radicals living in co-operative idyll. But in essence, this inter-war suburbanisation was the antithesis of the Garden City Movement, the sprawl of a city the very thing HowardŌĆÖs original model sought to prevent. One of the final suburban estates to be created before the Green Belt Act of 1938 stopped city expansion without limit was Dagenham ŌĆō home to and birthplace of Martin Gore before his familyŌĆÖs move to Basildon in the early 60s.

Dagenham was made up of 18,000 homes built by London County Council in the east of the city. There was nothing ŌĆśGarden CityŌĆÖ about it; there were few social amenities and no schools, hospitals, or shops. Families were left stranded, with a long, expensive commute to work. It became known as a ŌĆśnon-placeŌĆÖ.

The New Towns Programme held a greater respect for the Garden City MovementŌĆÖs core concept of the ŌĆ£best of town and countryŌĆØ in self-contained communities and coupled it with a new design for living that had risen to prominence in the 20s and 30s: the modernist movement. Spearheaded by Swiss architect Le Corbusier and symbolised by vast, brutal concrete constructions, the modernist movement would come to have a huge bearing on the architecture and philosophy of the New Towns. Le Corbusier envisaged modernism in its extreme form as a city for three million composed of large mega-blocks separated by freeways and linear parks. The house, he famously said, was as a machine for living in.

Cost was at the forefront of government thinking, and the modernist movement rationalised ŌĆō even celebrated ŌĆō low-cost terraces constructed from mass-production panel systems: houses imagined as large structures and sub-divided. Streets, estates, and whole neighbourhoods could be built simultaneously and mass-produced. This was how many of the estates of Basildon were planned and constructed.

In Stevenage, a public enquiry ran for three years before the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords eventually ruled in favour of the New Town policy as being in the national interest. The first New Town neighbourhood was not created there until 1956. By then Basildon was well underway, with over 2,500 new homes and almost 10,000 residents.

Built on an area of 18 square-miles located between (and covering) the existing towns of Laindon and Pitsea in south-east Essex, not far from Southend-on-Sea, Basildon was where the future began. It may have been the penultimate London New Town to be designated but it was the first to begin construction.

The seat of the Urban District Council (UDC) and local authority for the whole of the area was the nearby small town of Billericay. The top brass there had been unusually keen, unlike Stevenage council, to have a New Town built on their doorstep. Billericay UDC looked after a population of 42,500, and 25,000 of them lived in Laindon and Pitsea, small settlements where the majority of homes had no sewers, electricity, or mains water. The massive task of providing these basic amenities and making good the unmade roads in the area fell to the council.

Billericay Town Clerk Mr Alma Hatt canvassed tirelessly to make Basildon New Town happen and put pressure on the influential Essex County Council and the government. He was keen to impress upon them the fact that strong ties already existed with East and West Ham, since many of the ŌĆśplot-landŌĆÖ residents of Laindon and Pitsea had originally come from that area. He foresaw not just the solution to the councilŌĆÖs problems in Laindon and Pitsea but employment opportunities and a rise in council income from rates.

That sentiment was echoed in a letter written by Lewis Silken of provisional approval for the setting up of the New Town in Basildon, with ŌĆ£regard to the urgent need to find an outlet for the excess population and industry of the congested inner areas of East LondonŌĆØ. A delighted Hatt announced to the local press that Basildon would become the best town in Essex. Hatt goes down as the man who brought Basildon to life, and would later became known nationally when he oversaw a record turnaround of vote-counting for the Billericay constituency, which at the time still included Basildon, in the 1955 and 1959 general elections. The 1959 turnaround of 59 minutes has never been beaten. These results were said to be an indicator to which way the election would go. (In the late 70s and 80s, when ŌĆśBasildon ManŌĆÖ was talked about as a political phenomenon, the same idea re-emerged.)

Silken made clear that in selecting a name for the New Town he did not want reference to Laindon or Pitsea. He said the difficulties of those areas were best forgotten and dismissed the area as ŌĆ£not the brightest spot in the worldŌĆØ. But the ŌĆśplot-landersŌĆÖ of Laindon and Pitsea and the connected areas of Langdon Hills and Vange, and the tiny village of Basildon sandwiched between them, did not share that view. They felt theyŌĆÖd been sold out. To them the area was not some hillbilly backwater to be wiped off the map, but a version of their own rural arcadia. It was a frontier sort of place that had sprung up over four decades in ad hoc fashion. The whole of this part of Essex had once been typical farming country. The building of a direct railway line between London and the nearby seaside town of Southend, via Laindon and Pitsea, had coincided with the virtual collapse of farming in the late 1800s and radically transformed the landscape. Farmers sold their fields to land speculators, who in turn sold it off to the newly mobile working classes in individual plots, commonly just 18 square feet each.

The sales of these plots were heavily and misleadingly advertised in suburban newspapers and London railway stations. ŌĆ£Mains water readily availableŌĆØ often meant a standpipe a mile away; Pitsea was said to be so healthy that it didnŌĆÖt even have a doctor. The water in Vange, it was claimed, was a cure for rickets, stomach disorders, rheumatism, lumbago, and nervous disorders. On special occasions, free rail tickets from East Ham to Pitsea were issued; travellers were given a free lunch with champagne before the plot sales. Some deed owners never built on their land. After the generous hospitality on the train, some owners did not even realise they had purchased plots, or tore up contracts and threw them out of the carriage window on the way home.

Even so, a slow trickle of better-off people from the East End began to migrate to the area, with some of them building substantial two-storey brick villas. Others followed, with the less well-off building their own wooden and asbestos Shangri-Las in their tiny plots and spending weekends or summers blissfully free of the London smog.

Most of the land where Basildon New Town would sit was offered for sale between 1885 and 1910, but the much-vaulted ŌĆśchampagne salesŌĆÖ were not a huge success. Supply far exceeded demand. The plot-land sales boom came in the 20s and 30s; the area saw an influx of many thousands, mainly from LondonŌĆÖs East End. People with no agricultural experience dreamed of making a go of it on their own plots ŌĆō a rag-tag bunch of returning soldiers, the newly retired, or young idealists glad to escape London.

In the winter, the plot-lands became a muddy nightmare, but people could live with that for the sense of open space and freedom. Many of the plot-land shacks that were originally planned as weekend getaways became full-time homes, with their owners either subsisting off the land or commuting to London. Between 1921 and 1941, the population of the Billericay UDC area almost trebled, with the greatest increase taking place in the plot-land areas of Laindon and Pitsea. The completion of the A127 arterial road between London and Southend, and the A13 through Vange and Pitsea, further opened up the area.

A sprawl of shops popped up in Laindon and Pitsea to serve the growing population. It was still a rough and ready existence, lacking basic amenities, but with a cohesive community spirit: candles in jam jars, horse-and-cart deliveries, a network of footpaths. People dug their own wells, grew their own vegetables, and kept rabbits, chickens, and goats. The idea of making way for a vast modernist New Town and the threat of compulsory purchase orders did not go down well. According to the Residents Protection Association, which dubbed the New Town ŌĆśthe monsterŌĆÖ: ŌĆ£The loss of freehold would be a heartrending blow to those who have striven for years to acquire a small portion of their mother soil.ŌĆØ

Then, on October 7 1948, the Minster of Town and Country Planning himself, the Rt Hon Mr Lewis Silken MP, came to the district to speak at Laindon High Road School ŌĆō the school that Vince Clarke would later attend. Over 1,500 people turned up to hear Silken speak; many stood in the playground listening over loudspeakers. He invoked a sense of wider responsibility to the people of East and West Ham, ŌĆ£their own kith and kinŌĆØ, where, he said, one building in every four had been flattened by bombs and 20,000 people were on the waiting lists for homes.

He sympathised with those who built their own places at ŌĆ£great sacrificeŌĆØ and who wanted to spend the rest of their days in ŌĆ£peace and quietŌĆØ. His business, he said, was not to destroy but to build. He had no intention of pulling down (on a large-scale) buildings that already existed, but proposed to use the large area between Pitsea and Laindon to build the nucleus of a New Town.

ŌĆ£Basildon will become a city which people from all over the world will want to visit,ŌĆØ he proclaimed. ŌĆ£It will be a place where all classes of the community can meet freely together on equal terms and enjoy common cultural and recreational facilities. Basildon will not be a place which is ugly, grimy, and full of paving stones, like many modern towns. It will be something that the people deserve ŌĆō the best possible town that modern knowledge, commerce, science, and civilisation can produce.ŌĆØ

ąÜčāą┐ąĖčéčī ą╝ąŠąČąĮąŠ ą▓ąŠ ą▓čüąĄčģ ąĘą░čĆčāą▒ąĄąČąĮčŗčģ ąĖąĮč鹥čĆąĮąĄčé ą╝ą░ą│ą░ąĘąĖąĮą░čģ ąĖ ą║ąŠąĮąĄčćąĮąŠ ąĮą░ eBay ąĖ Amazone. ąĪčĆąĄą┤ąĮčÅčÅ čåąĄąĮą░ $10.

ą£čŗ čéą░ą║ ąČąĄ ą┐ąĖčüą░ą╗ąĖ ąŠ ąĄčæ čüąŠąĘą┤ą░ąĮąĖąĖ ą│ąŠą┤ ąĮą░ąĘą░ą┤, ą║ąŠą│ą┤ą░ ą╝ą░č鹥čĆąĖą░ą╗ č鹊ą╗čīą║ąŠ čüąŠą▒ąĖčĆą░ą╗čüčÅ. ąØąĄą╝ąĮąŠą│ąŠ ąĖčüč鹊čĆąĖąĖ ąĘą┤ąĄčüčī:

viewtopic.php?f=2&t=1229